by Emese Krunák-Hajagos

Abstract Expressionist New York

Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, May 28 – September 4, 2011

Abstract Expressionist New York considered a “killer” exhibition in Toronto showing the most important American art works of the 20th century. The exhibition is an open book of modern art history. It was exhibited first in New York titled The Big Picture (Museum of Modern Art, New York, October 3, 2010 – April 25, 2011) and is really a great bonus for Toronto to host a show at this scale and artistic importance in the summer.

Abstract Expressionism was the first specifically American movement to achieve worldwide recognition. In the late 1930s and through World War II many leading painters fled the terrors of Nazism in Europe and sought refuge in the United States. Among them were Hans Hoffman, who became a pioneer and teacher of abstraction and Archile Gorky, the “godfather” of the movement. While the war was raging in Europe, New York City was a safe haven. Exiled artists and dealers filled the city. Peggy Guggenheim opened her gallery The Art of This Century, Leo Castelli became an art dealer and local artists all benefitted. At the end of the war, Europe was in ruins and New York replaced Paris as the centre of the art world. The United States came out of the war victorious and its economy was stronger than ever. Some kind of hero worship was in the air and the Americans were ready to develop their national identity even further and show their importance to the world. A new generation of American artists began to emerge and soon they would be ready to dominate the world stage. They were called the New York School or the Abstract Expressionists, a new term the art critic Robert Coates used to describe Hofmann’s works in 1946. All the artists felt an urgency to depict, look at, think about and make art of their time. As Jackson Pollock said, “It seems to me that the modern painter cannot express this age, the airplane, the atom bomb, the radio, in the old forms of the Renaissance or of any other past culture. Each age finds its own techniques.”

![Jackson Pollock;Jackson Pollock [Misc.]](http://www.artoronto.ca/wp-content/uploads/2011/08/Pollock.jpg) Artist Jackson Pollock working in his studio. Photo by Martha Holmes/Time Life Pictures/Getty images

Artist Jackson Pollock working in his studio. Photo by Martha Holmes/Time Life Pictures/Getty images

“We agree only to disagree”could be the unwritten motto of this loose grouping of artists according to the art historian Irving Sandler. As the Abstract Expressionists never formed a unified group, their diversity was always visible. In the 1940s, the two leading critics of Abstract Expressionism, Clement Greenberg and Harold Rosenberg had different theories about the meaning, function and style of modern art that created an ongoing debate. Greenberg defined painting by its flatness, so it had to be purified of all illusionistic and sculptural effects such as deepness and plasticity. Subject matter also had to be eliminated. He urged the artists to develop “a bland, large, balanced, Apollonian art” aiming for “an intense detachment” from everything present—a rather minimalist approach. Greenberg advocated for Jackson Pollock and the Color field painters like Mark Rothko, Barnett Newman, Adolf Gottlieb, Clyfford Still and Hans Hofmann. However artists had little sympathy for his formalist perspective, as Rothko wrote in a letter to the New York Times in 1943: “It is widely accepted notion among painters that it does not matter what one paints so long as it is well painted… There is not such a thing as good painting about nothing.” Harold Rosenberg was more interested in the political and social movements of the period and their influence on the artists. He spoke of the transformation of painting into an existential drama: “At a certain moment the canvas began to appear to one American painter after another as an arena in which to act. What was to go on the canvas was not a picture but an event.” Action painting is a term created to describe the works of Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning and Franz Kline. Then came the big moment when it was painting for just the sake of PAINT and the gesture on the canvas was liberation from political, aesthetic and moral values.

Abstract Expressionism and MoMA came into being about the same time. In the 1940s director Alfred H. Barr, Jr. started to collect works from his artist friends; being there at the moment when their first exhibition opened; artist and curator building institutional and art history at the same time. As MoMA’s director Glenn Lowry said what made that time unique “was a capacity of artists to engage with a cosmic quest, a spiritual quest to find meaning.” “A total commitment on the artists’ side” continued Ann Temkin – “painting was the only thing that mattered there was no separation between the self and the art work, that’s why the paintings feel like living things.” The exhibited works in this show all came from MoMA’s collection curated by Ann Temkin. Her goal was finding the layers underneath the surface and show the artists’ works before they became “big”, documenting the whole artistic development not just the trophy pieces. The New York and Toronto exhibitions are differently installed and that somehow changes the outcome. There are less works in numbers in Toronto still the show is as strong, even more focused, since the most important, strongest pieces are here.

Arshile Gorky (American, born Armenia. 1904-1948), Garden in Sochi; c. 194;3 Oil on canvas; 31 x 39″ (78.7 x 99 cm)The Museum of Modern Art. Acquired through the Lillie P. Bliss Bequest 492.1969 © 2010 The Arshile Gorky Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York Photo Credit: The Museum of Modern Art, Department of Imaging Services, Paige Knigh

Arshile Gorky (American, born Armenia. 1904-1948), Garden in Sochi; c. 194;3 Oil on canvas; 31 x 39″ (78.7 x 99 cm)The Museum of Modern Art. Acquired through the Lillie P. Bliss Bequest 492.1969 © 2010 The Arshile Gorky Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York Photo Credit: The Museum of Modern Art, Department of Imaging Services, Paige Knigh

As we walk into a narrow corridor at the beginning of the show we see the early mythological works of William Baziotes (Dwarf, 1947) and Adolf Gottlieb. Achile Gorky’s late works like Garden in Sochi (1938-40) refers to the artist’s past and the memories of it. His images are more delicate and more outlined then earlier in his carrier with a vibrant palette. His figures go through a methamorphosis and are becoming floral like creatures and even a composition like Agony (1947) seems almost happy.

Willem de Kooning (American, born the Netherlands.1904-1997) Woman, I.; 1950-52; Oil on canvas; 6′ 3 7/8″ x x58″ (192.7×147.3 cm). The Museum of Modern Art. Purchase 478.19532010 The Willem de Kooning Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York Photo Credit: The Museum of Modern Art, Department of Imaging Services, John Wronn

Willem de Kooning (American, born the Netherlands.1904-1997) Woman, I.; 1950-52; Oil on canvas; 6′ 3 7/8″ x x58″ (192.7×147.3 cm). The Museum of Modern Art. Purchase 478.19532010 The Willem de Kooning Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York Photo Credit: The Museum of Modern Art, Department of Imaging Services, John Wronn

Willem de Kooning is represented by only three paintings hanging in the same small room; they were placed in three separate galleries in New York. It is even more visible here how he never applied himself to any style keeping his artistic freedom, switching between abstraction and figurativity. The famous Woman I, (1950), a strong figurative piece, is much disputed. Does it picture the scary, overwhelming aspect of female power over men or does it mirror male aggression toward women? The large figure of the woman with enormous breasts, big eyes and howling mouth is depicted by angry brush strokes while her clothes and the background are created by abstract patches of paint.

Jackson Pollock (American, 1912-1956), The She-Wolf, 1943; Oil, gouache, and plaster on canvas41 7/8 x 67″ (106.4 x 170.2 cm) .The Museum of Modern Art. Purchaces2011 The Pollock-Krasner Foundation/Artists Right Society (ARS), New York:Photo credit: The Museum of Modern Art, Department of Imaging Services

Jackson Pollock (American, 1912-1956), The She-Wolf, 1943; Oil, gouache, and plaster on canvas41 7/8 x 67″ (106.4 x 170.2 cm) .The Museum of Modern Art. Purchaces2011 The Pollock-Krasner Foundation/Artists Right Society (ARS), New York:Photo credit: The Museum of Modern Art, Department of Imaging Services

A large gallery is dedicated to Jackson Pollock’s paintings. His early canvases (Mask, 1941) remind us of Picasso and his first really original piece is The She-Wolf (1943) with its free-form abstraction. In 1947, Pollock described his painting process in detail: “I prefer to tack the unstretched canvas to the hard wall or the floor. I need a resistance of a hard surface. On the floor I am more at ease. I feel nearer, more a part of the painting, since this way I can walk around it, work from the sides and literally be in the painting.” Pollock used objects such as sticks, spatulas, knives, or vessels with which the paint could be dripped, poured or hurled on the canvas. He emphasized the automatism of his approach as a “pure harmony, an easy give and take” but also mentioned that after a “get acquainted period” with the painting he makes changes, and has no fear of destroying part of the composition since the painting has its own life and comes out well at the end. Full Fathom Five (1947) is a good example of this method. The weave of the top colour-layers veils a figure painted with lead paint. The objects worked into the picture such as buttons, keys, nails, cigarettes etc. are placed with reference to this hidden figure, you can see them at a close observation.

Jackson Pollock (American, 1912-1956), Number 1A, 1948; 1948; Oil and enamel paint on canvas; 68″ x 8′ 8″ (172.7 x 264.2 cm). The Museum of Modern Art. Purchase ©2010 The Pollock- Krasner Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New YorkPhoto Credit: The Museum of Modern Art, Department of Imaging Services

Jackson Pollock (American, 1912-1956), Number 1A, 1948; 1948; Oil and enamel paint on canvas; 68″ x 8′ 8″ (172.7 x 264.2 cm). The Museum of Modern Art. Purchase ©2010 The Pollock- Krasner Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New YorkPhoto Credit: The Museum of Modern Art, Department of Imaging Services

Pollock painted with his whole body, moving fast in a dance-like trance around the canvas, dripping or throwing paint sometimes straight from the can, then quickly touching it up, radiating a strong physical energy. His new painting method was a revelation to the New York art scene and in August, 1949 Life Magazine named him the greatest living painter in the United States. It was a hard responsibility to shoulder. In July 1950 Hans Namuth photographed and filmed him at work and his pictures created the mythic, sexually-charged image of “Jack the Dripper.” Pollock became a hero of mass media and someone called his drip-painting an “apocalyptic wallpaper.” Pollock didn’t mean to create decor, still his “all over” method—covering the entire surface of the canvas and giving each part an equal importance (White Light, 1954)—became very influential for ornamental and decorative styles. The art critic Robert Hughes wrote that as his work was so influential, his image as a man was too. The image of a world famous painter, the Vincent van Gogh from Wyoming, dying at forty-four, drunk, with two girls in a big, expensive car, was elevated to symbolism as it is depicted in the actor and director Ed Harris’ movie: Pollock (2000).

Mark Rothko is represented in a large gallery. Slow Swirl at Edge of Sea (1945), a surrealistic composition with two humanlike forms embraced in a swirling, floating, dancing happiness, depicted by soft grays and browns. In 1950 he started to paint his “multiforms,” his signature paintings. Rothko usually divided the canvas into three horizontal planes of bright, vibrant colours. He applied a thin layer of binder mixed with pigment onto the bare canvas, and then painted thinned oils onto this layer, then another layer, creating a dense mixture of overlapping colours and shapes which bleed into each other. His brushstrokes were light and very fast. A dramatic effect is created by the contrast of colours, radiating with inner energy (No.5/No.22, 1950).

Mark Rothko (American, born Latvia. 1903-1970), No. 5/No. 22; 1950 (dated on reverse 1949); Oil on canvas; 9′ 9″ x 8′ 11 1/8″ (297 x 272 cm). The Museum of Modern Art. Gift of the artist.© 1998 Kate Rothko Prizel & Christopher Rothko / ArtistsRights Society (ARS), New York.Photo credit: The Museum of Modern Art, Department of Imaging Services

Mark Rothko (American, born Latvia. 1903-1970), No. 5/No. 22; 1950 (dated on reverse 1949); Oil on canvas; 9′ 9″ x 8′ 11 1/8″ (297 x 272 cm). The Museum of Modern Art. Gift of the artist.© 1998 Kate Rothko Prizel & Christopher Rothko / ArtistsRights Society (ARS), New York.Photo credit: The Museum of Modern Art, Department of Imaging Services

As Rothko wrote, his paintings are “only expressing basic human emotions – tragedy, ecstasy, doom and so on… The people who weep before my pictures are having the same religious experience I had when I painted them.” There is really something religious in Rothko’s attempt to abandon everything to feelings and create an unworldly atmosphere in his paintings No.37 Slate Blue and Brown on Plum (1958) gives a feeling of deepness and almost invites you to step into the blue shape and disappear into another world. Rothko became famous, successful and rich, and ironically that deepened his depression. The luxurious New York Four Seasons Restaurant’s commission (1958), well depicted in the Broadway show Red, was a great painterly challenge and his personal undoing at the same time. He never delivered the 40 pieces he painted for them. In the 1960s his horizon darkened dramatically. He finished the 14 large, dark, blood-coloured canvases for the Rothko Chapel but committed suicide before they were installed in 1971.

A gallery shows a few works of Barnett Newman starting with Onement, I (1952), his breakthrough painting. The surface of a monochromatic background is vertically divided in half by an orange band, a “zip,” as the artist later called it. Newman explained his zip motive in his essay The First Man Was an Artist, as the stick the aboriginal man used to draw a line in the mud. Newman suggested that his zip should be taken as a metaphor for this primal and tragic gesture of art. There is a photograph by Robert Frank showing a New York street with a white line in the middle (Street Line, New York, 1951); an interesting example of how a similar motive surfaces with different meanings in different artists’ works.

Franz Kline (American, 1910-1962), Chief,1950; Oil on canvas; 58 3/8″ x 6′ 1 1/2″ (148.3 x 186.7 cm). The Museum of Modern Art. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. David M. Solinger. © 2010 The Franz Kline Estate / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo credit: The Museum of Modern Art, Department of Imaging Services, John Wronn

Franz Kline (American, 1910-1962), Chief,1950; Oil on canvas; 58 3/8″ x 6′ 1 1/2″ (148.3 x 186.7 cm). The Museum of Modern Art. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. David M. Solinger. © 2010 The Franz Kline Estate / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo credit: The Museum of Modern Art, Department of Imaging Services, John Wronn

There are excellent pieces from Clyfford Still, Franz Kline and Robert Motherwell representing a more simplified, but not simple, gestural painting style which influenced the future artist generation greatly. Refreshing with its humour Isamu Noguchi’s Even the Centipede, (1957) stoneware sculpture with its long body and many legs created of plates, kettles and various pots. Abstract Expressionism involved many female artists as well. Lee Krasner greatest paintings were created after her husband Pollock’s death, Gaea, 1966, among them with its dynamic red and black waves. On Joan Mitchell’s large canvas titled Ladybug, 1957 fast, free-swinging brushstrokes try to follow the color illusion created by the fly of the bug.

Joan Mitchell (American, 1925-1992). Ladybug, 1957; Oil on canvas;6′ 5 7/8″ x 9′ (197.9 x 274 cm). The Museum of Modern Art. Purchase © Estate of Joan Mitchell.Photo credit: The Museum of Modern Art, Department of Imaging Services, Thomas Griesel

Joan Mitchell (American, 1925-1992). Ladybug, 1957; Oil on canvas;6′ 5 7/8″ x 9′ (197.9 x 274 cm). The Museum of Modern Art. Purchase © Estate of Joan Mitchell.Photo credit: The Museum of Modern Art, Department of Imaging Services, Thomas Griesel

In the last room, the Canadian born Philip Guston begun with pure painterly gestures, to start and finish his canvases in one session, not to stop, not to look at it, just stay close to it and paint, which produced one of the happiest painting I’ve ever seen (Painting, 1954) with its deep, energetic, pink strokes. Later he decided to depart from abstractionism in order to tell stories in cartoonlike compositions (Edge of town, 1969) and his painting is the last work in this amazing show.

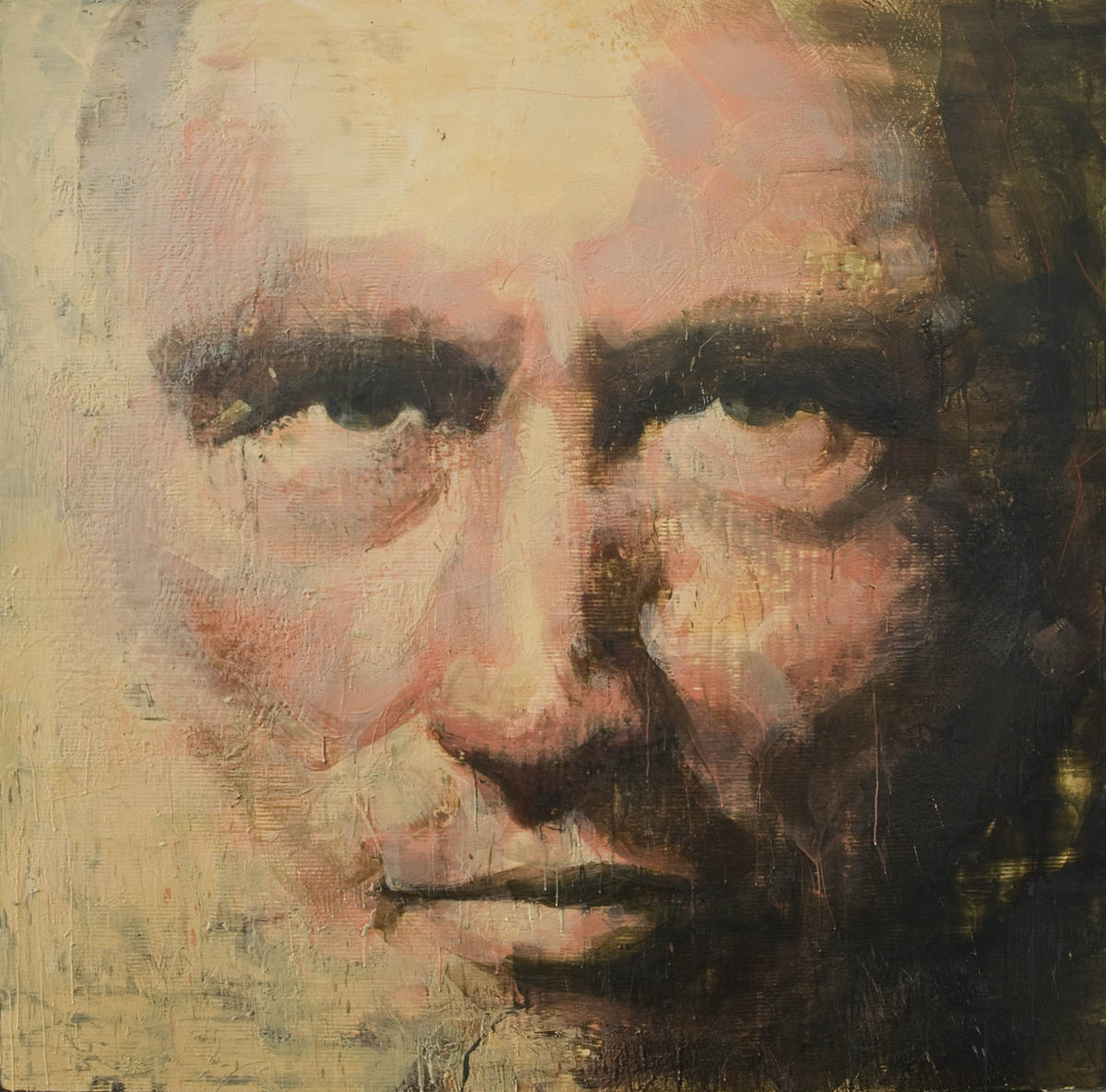

Trudeau, 2010-11, encaustic, oil pastel on canvas, 84 x 84 in. Courtesy of Georgia Scherman Projects, Toronto

Trudeau, 2010-11, encaustic, oil pastel on canvas, 84 x 84 in. Courtesy of Georgia Scherman Projects, Toronto Machiavelli, 2010-11, encaustic, oil pastel on canvas, 84 x 72 in. Courtesy of Georgia Scherman Projects, Toronto

Machiavelli, 2010-11, encaustic, oil pastel on canvas, 84 x 72 in. Courtesy of Georgia Scherman Projects, Toronto Nun, 2010-11, encaustic, oil pastel on canvas, 54 x 60 in. Courtesy of Georgia Scherman Projects, Toronto

Nun, 2010-11, encaustic, oil pastel on canvas, 54 x 60 in. Courtesy of Georgia Scherman Projects, Toronto

![Jackson Pollock;Jackson Pollock [Misc.]](http://www.artoronto.ca/wp-content/uploads/2011/08/Pollock.jpg)