By Ashley Johnson

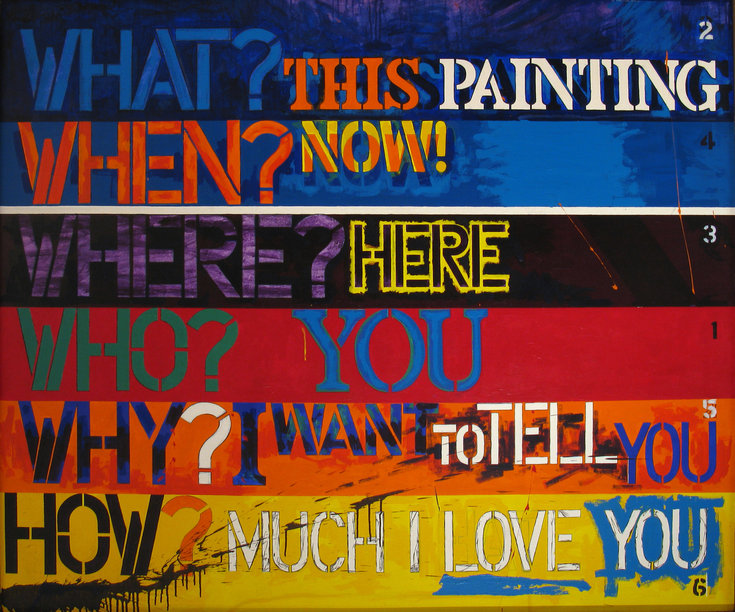

Six Questions, 1976, acrylic on canvas, 60 x 72 inches. Courtesy of Christopher Cutts Gallery

Six Questions, 1976, acrylic on canvas, 60 x 72 inches. Courtesy of Christopher Cutts Gallery

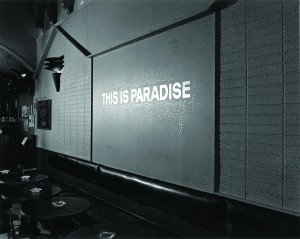

An exhibition in conjunction with THIS IS PARADISE, Mocca, 2011

Christopher Cutts Gallery,

June 25 – August 31, 2011

A sign of cultural maturity in developed societies is the wholehearted support and celebration of its artists. Their contribution is recognized as ‘cultural capital’, to be nurtured and exported, whether as art objects or social ideas. Value is attached and upheld by institutions that generate knowledge and shows about that product. A case in point is the current Abstract Expressionist exhibition at the AGO, orchestrated by MOMA (NY).

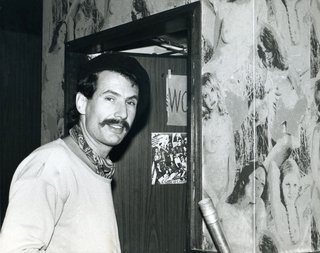

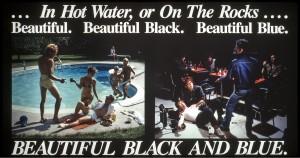

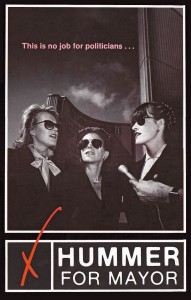

THIS IS PARADISE seeks to re-present the 80’s art scene in Queen Street West and is linked to Dennis Burton’s show, ‘Word Magic’ at the Christopher Cutts Gallery, because Burton taught some of the artists in the 60’s and 70’s at The New School of Art and Art’s Sake. That said, it’s an extremely tenuous connection artistically because the artists in THIS IS PARADISE represent mainly figuration, exemplified by the group Chromazone, whereas Burton’s art and teaching runs the gamut of modernism. A cursory glance at Burton’s extraordinary contribution both as an artist and as an educator makes one wonder why the institutional acknowledgement of these decades is so understated. The conjunction highlights the immaturity of this society.

Alchemy, 1978, acrylic on canvas, 60 x 60 inches. Courtesy of Christopher Cutts Gallery

Alchemy, 1978, acrylic on canvas, 60 x 60 inches. Courtesy of Christopher Cutts Gallery

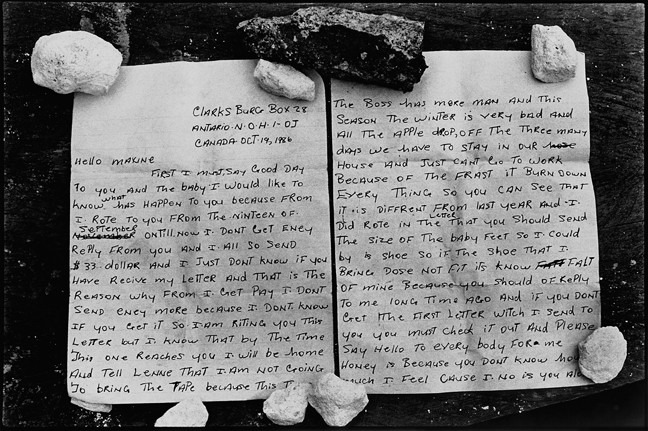

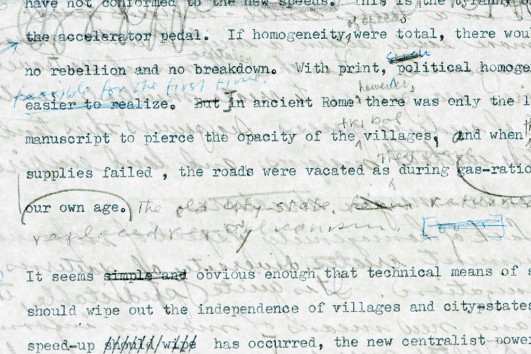

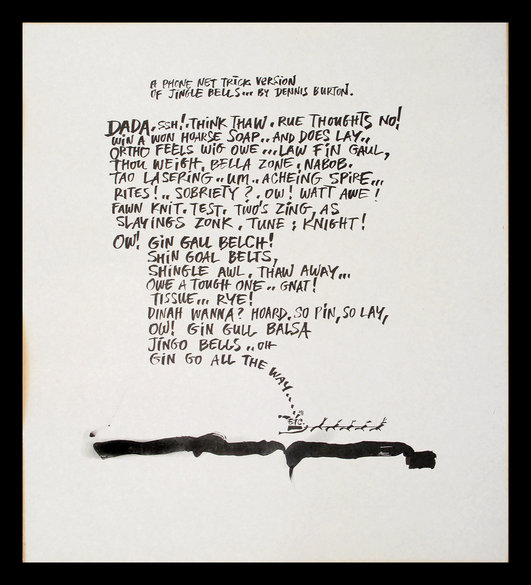

Burton uses words like a mechanic greasing an axle, fluidly and with some abandon. They lose their form and meaning, becoming sound poems generating new meanings through chance juxtapositions. Duchamp is ‘in the room’. There is an innate beauty to Burton’s writing style, which oscillates between making shapes out of words to laboriously etching text into every available space on the page. He loves words sensuously.

Jingle bells circa 1965, on paper, 18 x 16 inches

Jingle bells circa 1965, on paper, 18 x 16 inches

Courtesy of Christopher Cutts Gallery

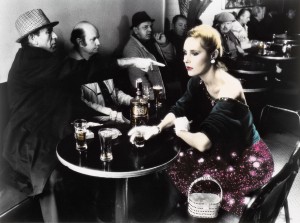

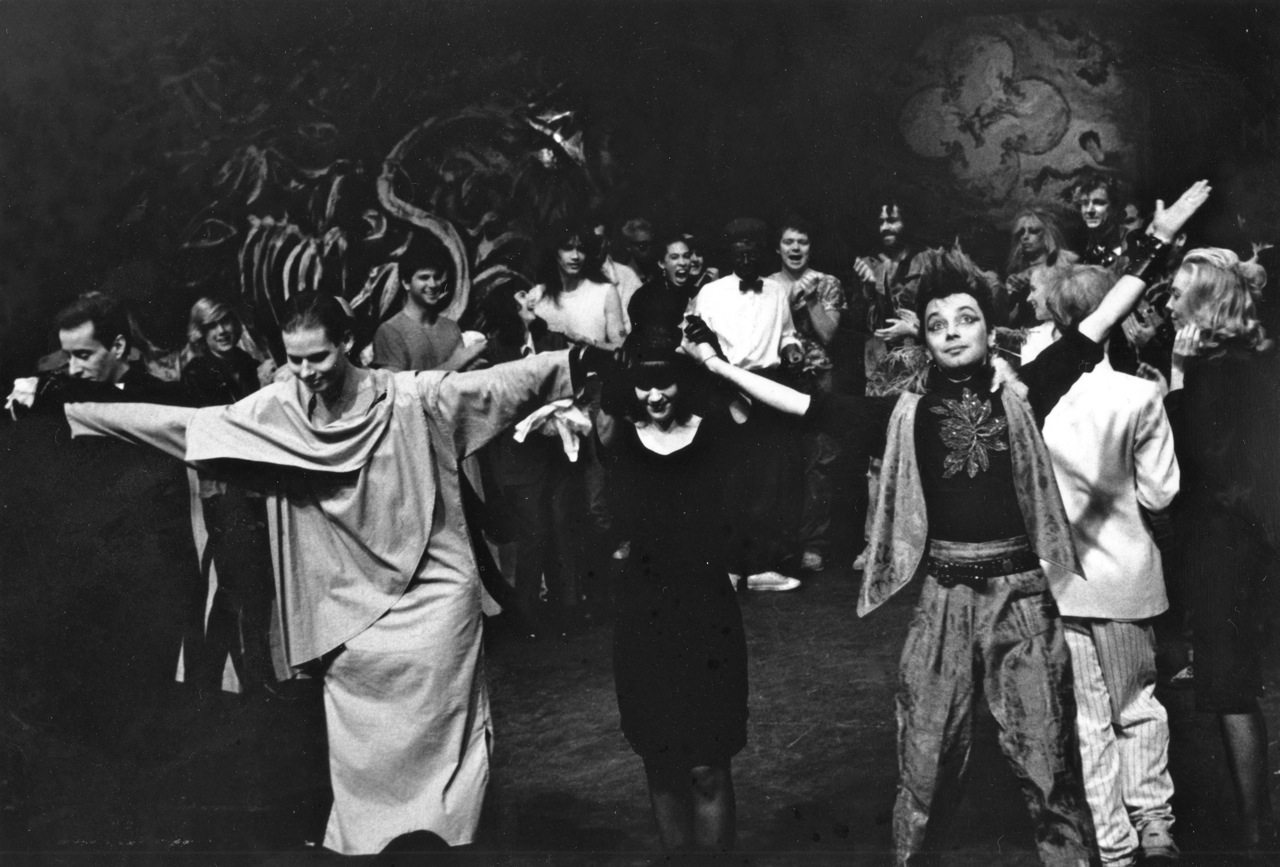

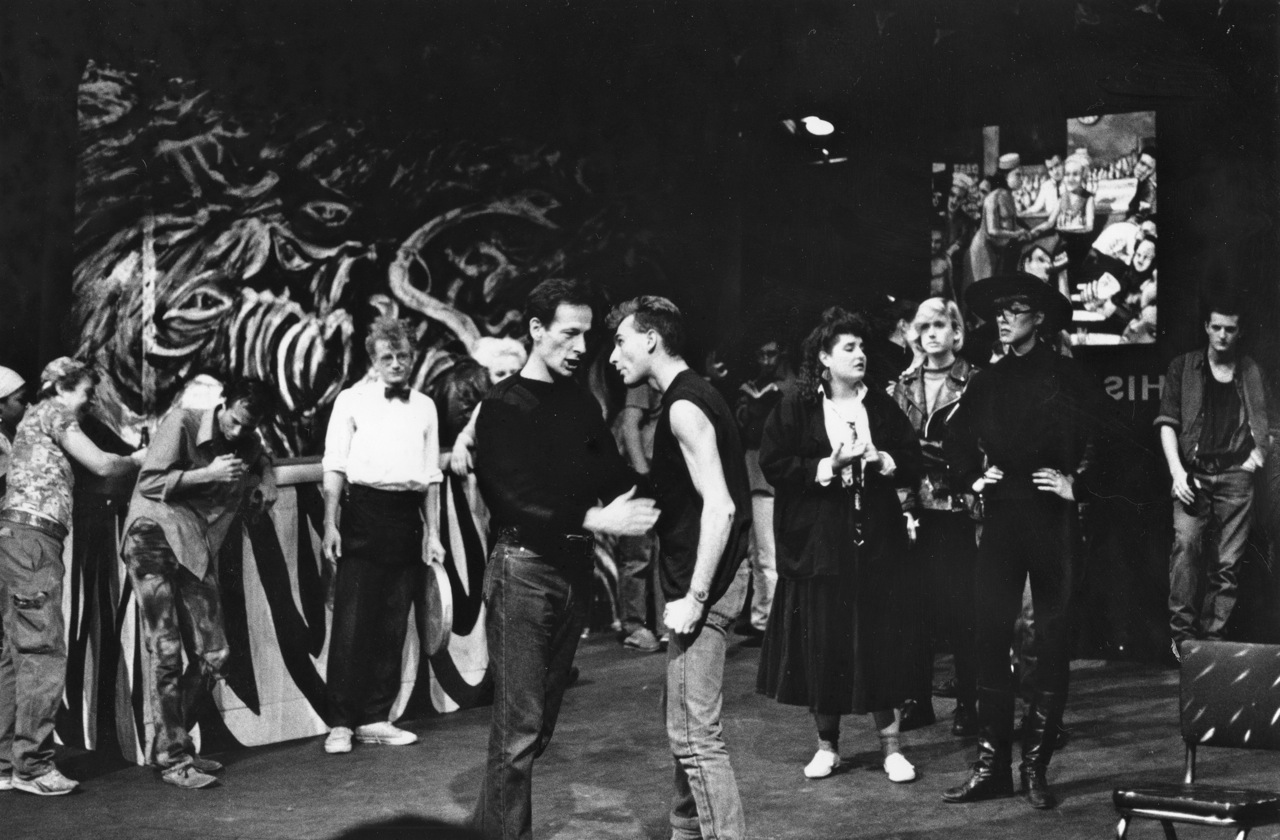

There are some very absorbing framed texts in which Burton answers questions put by Rae Johnson and Brian Burnett about his experiences after graduating from OCA. It’s astounding to learn that the fine-arts program was abandoned by OCA in 1956 in favour of design elements. This galvanized Burton and his colleagues in 1965 to begin teaching art at The New School of Art and later Art’s Sake. There is something heroic in Burton’s efforts to survive monetarily and still teach students to become practicing artists. He is apparently remembered for his erudite lectures that synthesized knowledge from all spheres. Uniquely, his colleagues included artists actively working at their profession like Gordon Rayner, Robert Markle and others who all achieved some local notoriety. The schools sound like hotbeds of creativity and fun, with the Artist’s Jazz Band performing alongside theatre events. There are taverns like the Cameron House that became cultural meeting places. The roles of galleries such as Av Isaacs and Dorothy Cameron are mentioned. Censorship rears its head when police confiscate works and the artists go on trial but charges are later dismissed. In this period Burton made erotic images of women in a series called Garterbeltmania. They seem quite inoffensive and rather beautiful now.

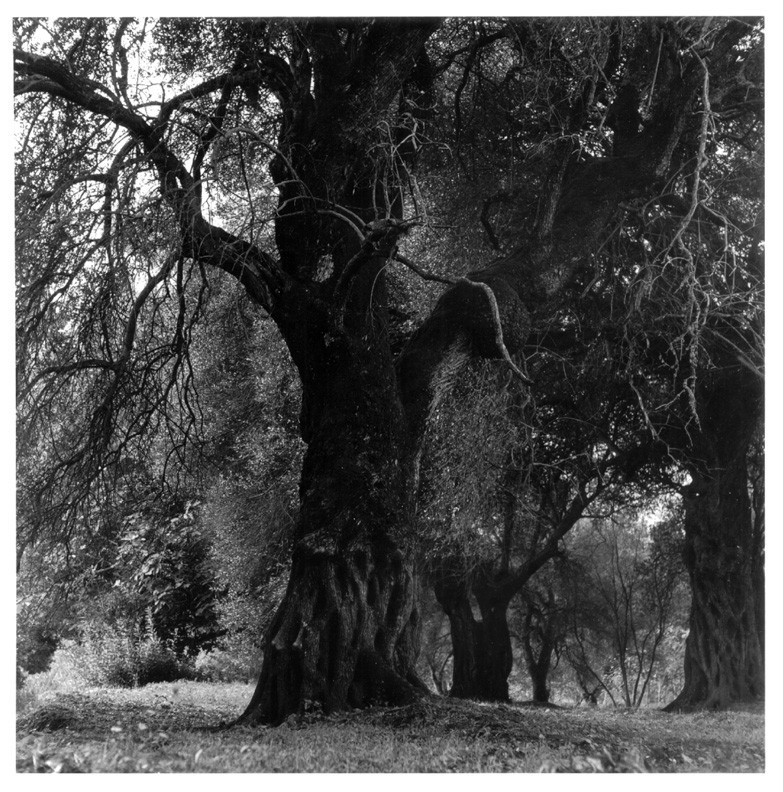

Stripe Streak, 1977, acrylic on canvas, 49 x 98 inches. Courtesy of Christopher Cutts Gallery

Stripe Streak, 1977, acrylic on canvas, 49 x 98 inches. Courtesy of Christopher Cutts Gallery

The paintings in this show remind me of Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns’ work except Burton’s are more text based. They share an anomalous position in my mind as not quite ‘Pop Art’ yet vital in their Dadaistic ‘clawing back’ meaning from the excesses of Abstract Expressionist theory. Burton’s words have a humanity that reaches out, as in his painting Six Questions, which ends in an expression of love for … perhaps the viewer. In Stripe Streak he plays with meaning and action ironically. The self-importance of post painterly abstraction is gently and humorously debunked.

Glancing at Burton’s timeline on the ccca.ca website, one is left wishing to see a more comprehensive retrospective of the era and his art. It would be a pity if this history just lapses into obscurity. Fifty-odd years have already passed so it’s about time!

Workers in a sock factory in Toronto’s garment district. From Not Paved with Gold: Italian-Canadian Immigrants in the 1970s ©Vincenzo Pietropaolo

Workers in a sock factory in Toronto’s garment district. From Not Paved with Gold: Italian-Canadian Immigrants in the 1970s ©Vincenzo Pietropaolo